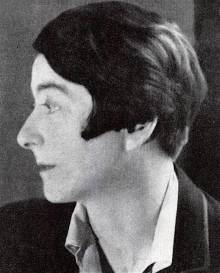

Eileen Gray was born Kathleen Eileen Moray Smith [the family surname was changed to Gray in 1893] in Brownswood, near Enniscorthy in County Wexford, Ireland on 9 August 1878. In 1898 she began studying painting the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London [Note: according to 'Eleen Gray' by Caroline Constant (London: Phaidon, 2000), Gray first enrolled at the Slade until 1901], but, following the death of her father in 1900 left for Paris. Over the next six years she divided her time between Paris, London and her family home in Ireland. During this period she attended the Académie Julian and the Académie Colarossi in Paris and spent further time at the Slade. However, she became increasingly disinterested in painting and drawing. By chance she discovered the art of lacquerwork having visited Mr D. Charles' lacquer repair shop in London's Soho district. Lacquer became her new passion. In 1906 Gray returned to Paris and from 1907 to c.1911 trained as a lacquer artist with Seizo Sugawara, a Japanese artisan who had emigrated to France in 1898 to work on the Japanese pavilion at the Paris Exposition of 1900.

In 1909 with and a friend, Evelyn Wyld (1882-1973) [an American designer who had settled in Paris in 1907], Gray visited North Africa where she learned the technique of wool dying from Moroccan craftswomen. The following year she and Wyld opened a weaving workshop at 17, rue Visconti in Paris, and, with Sugawara, she established lacquer workshop at 11, rue Guénégaud in Paris. In 1911, with her sister, Thora, and two friends, Gray visited the USA. In 1913, she exhibited examples of her lacquerwork - screens and a library panel, at the VII Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in Paris. She also attracted her first important client, the French fashion designer, connoisseur and art collector, Jacques Doucet (1853-1923), who purchased pieces by her for his Paris apartment.

When war broke out in 1914, Gray enlisted as an ambulance driver. In 1915 she went back to London, taking Sugawara with her. Together they opened a lacquer workshop in Chelsea. Failing to attract sufficient clients, in 1917 they returned to Paris where Grey reopened her lacquer and weaving workshops. In 1919 she received a commission to decorate the apartment of Suzanne Talbot (Madame Mathieu Mathieu-Lévy) on rue de Lota, Paris [project completed in 1922], and exhibited at the X Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in Paris.

In 1921 she met the Romanian-born architect and architectural critic Jean Badovici (1893-1956). In 1922 the pair opened a shop, Galerie Jean Désert, at 217, rue du Fauborg-St-Honoré in Paris sold furniture and rugs designed by Gray, as well as pieces designed by Wyld and Sugawara. Later that year Gray exhibited a lacquer screen, chest of drawers, two carpets, and a wall hanging at the Salon d'Automne in Paris. In 1923 the Boudour de Monte Carlo, a tour de force in lacquer designed by her, was installed at the XV Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in Paris. While disliked by the French critics it was admired by the Dutch architect J.J.P. Oud (1890-1963), which may have led to the publication of a special issue on Gray by the influential Dutch magazine 'Wendingen' the next year. In 1924 she created wall hangings of an installation by Pierre Chareau (1883-1954) at the XV Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in Paris.

In 1926, encouraged by Badovici, Gray turned to architecture as another outlet for her creative ideas. Between 1927-29 they worked together on the design and furnishing of E-1027, Gray's villa at Roquebrune, Cap Martin, France. The house and its furnishing attracted considerable attention in the architectural press, and in 1929 was the subject of a special issue of 'L'Architecture Vivant'. It also featured in the first exhibition of the Union des Artistes Modernes (UAM) in Paris in 1930. Gray and Badovici also worked on a number of renovation projects in the late 1920s and early 1930s, including Badovici's house in Vézelay, which featured in the second UAM exhibition in 1931.

Between 1932-34 Gray worked on her second significant architectural project, Tempe à Pailla, her villa at Castellar, near Menton, France, for which she also designed the furnishing. Architectural and furniture design schemes by her were displayed at the XXIV Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in Paris in 1933 and at the Salon d'Automne in Paris that year.

In 1934 Gray and Badovici visited New York and Mexico. In 1936-37 Gray worked on two more significant architectural projects - the Ellipse House, a low-cost housing unit, and a concept for a vacation and leisure centre. The later project was displayed in Le Corbusier's Pavillon des Temps Nouveau at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris in 1937. The outbreak of World War Two effectively marked the end of Gray's career as a designer, and, thereafter, few of her architectural projects were realised. In 1944 her apartment in Saint-Tropez, together with many of her architectural drawings, were destroyed by bombing. Her significance as an architect and designer was appreciated with the publication of an article on her work by Joseph Rykwert in the Italian architectural journal 'Domus' in 1968. Several books and articles followed and in 1972 she was recognised by the Royal Society of Arts in London who elected her a Royal Designer for Industry (RDI). The following year she was the subject of a major retrospective exhibition at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in London, and in 1973 an exhibition of her architecture toured the USA. She was also elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland.

Gray died in Paris on 28 November 1976.

Examples of her work are included in the permanent collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London; and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Adam, Peter. Adjustable table E1027 by Eileen Gray. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Form Verlag, 1998

Adam, Peter. Eileen Gray: her life and work. Munich, Germany: Schirmer/Mosel Verlag, 2009

Baudot, François. Eileen Gray. Paris: Assouline, 1998

'Complete designer: the work of Eileen Gray'. Design no.289, January 1973 pp. 68-73

Constant, Caroline. Eileen Gray. London: Phaidon, 2000

Constant, Caroline and Wang, Wilford. Eileen Gray: an architecture for all senses. Berlin: Wasmuth, 1996

Doumato, Lamia. Eileen Gray 1879-1976. Monticello, Illinois: Vance Bibliographies, 1981

'Eileen Gray: a neglected pioneer of modern design'. RIBA Journal vol. 60, February 1973 pp.68-69

Eileen Gray. Introduction by Jans wils with accompanying text by Jean Badovici. ‘Wendingen’ no.6, 1924 [A special issue of Wendingen

Garner, Philippe. Eileen Gray: designer and architect 1878-1976. Cologne, Germany: Taschen, 1993

Garner, Philippe. 'The lacquer work of Eileen Gray and Jean Dunand'. Connoisseu bvol.189, May 1973 pp.2-11

Gray, David. 'The complete designer'. Design no. 289, January 1973 pp.68-73

'Gray: Victoria and Albert Museum, London exhibit' Architects Journal vol. 169, February 1973 pp.68-69

Hecker, Stefan, et al. Eileen Gray. Barcelona, Spain: Gustavo Gili, 1993

Johnson, J. Stewart. Eileen Gray, designer. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1979

Kay, J. H. 'Who is Eileen Gray and are you sitting in one of her chairs?' Ms. 4 April 1976 pp.80-83

Moore, Rowan. 'Design: Eileen Gay'. Vogue [UK] January 1988 pp.32-33

Naylor, Gillian. 'Eminence grise' Design March 1988 p.50

Pitiot, Cloe, et al. Eileen Gray, Designer and Architect: An Alternative History. New Haven; London: Yale University Press/Bard Graduate Center, 2020 [ISBN 10: 0300251068 / ISBN 13: 9780300251067]

Rowlands, Penelope. Eileen Gray. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books, 2002

Rykwert, Joseph. 'Eileen Gray: pioneer of design'. Architectural Review vol.152, December 1972 pp. 357-361

Rykwert, Joseph. 'Eileen Gray: two houses and an interior 1926-1933' Perspecta nos. 13-14, 1971 pp.66-73

Snoddy, Theo. Dictionary of Irish Artists 20th Century. Dublin: Merlin Press, second edition, 2002 pp. 205-207

Teitelbaum, Mo. 'Lady of the rue Bonaparte' The Sunday Times Magazine 22 June 1975 pp. 28-32, 40